Today we complete our tales about the amazing frescoes of the Sistine Chapel.

In the past weeks, we already mentioned the 15th-century frescoes painted by incredible artists, such as Botticelli and Perugino, and the ceiling painted by Michelangelo with the nine main scenes from the book of Genesis. Today we focus on the last mesmerizing wall of the chapel, painted again by Michelangelo thirty years after the ceiling.

The history of the Sistine Chapel could well have ended on 30 October 1512. Instead, it continued and terminated more than a quarter of a century later, when the Judgement time came, the supreme work of the later years completed by Michelangelo between 1536 and 1541, under Pope Paul III Farnese.¹

In those years, Italy and Europe had profoundly changed compared to the “ golden age” of Julius II. In 1527, there had been the Sack of Rome, and the spiritual unity of the West had been broken forever following the evangelical Reformation; the Catholic Church was on the defense, preparing the Council of Trent and organizing the tough and shrewd re-conquest which manuals refer as the Counter-Reformation; impoverished Italy, now under the political control of the great powers, was, with the sole exception of Venice, a country with limited sovereignty.

The Last Judgement took five years to complete, from 1536 to 1541. The iconographic subject was in a sense obligatory. If the Sistine Chapel as a whole tells the history and destiny of Man created by God and entrusted to the redeeming guidance of the Church – after the Genesis, after the affirmation of the Laws of Christ which integrate and surpass the Law of Moses, after the series of popes who by divine mandate have the power of the keys and therefore the power to loosen and bind – after all this, the Judgement could hardly go missing, the end of the Story for every and each one us.

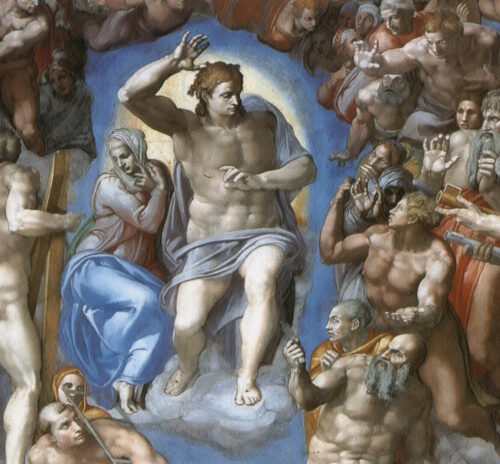

Judgment is the term by which the great fresco is universally known. The term is correct but it would be better to call it the Parousia; the Second Coming of Christ on earth to judge the living and the dead, to forever erase things, Time and History.

Whosoever beholds the Judgement has the impression there is no wall, but that the gaze opens onto an indefinite space, made up of icy, light blue air. In this unrealistic, metaphysical dimension, where Time is no more because History is over, everything happens at the same time: the Resurrection of the Dead and Judgement, Hell and Paradise.

Michelangelo’s judge does not sit on a throne; he is beardless; he has the look of a young glorious and victorious athlete, but the painter was able to represent with extraordinary effectiveness the theological anguish of the Parousia. Time is over, History is no more. The Church too has fulfilled its task. Peter returns to Christ the keys which had been given to him, just like in Perugino’s painting of so many years before.

Even the Virgin Mary no longer has a role. She clings resigned to her Son because her task as Mother of Mercy, Gate of Heaven, the Refuge of Sinners and Comforter of the Afflicted is definitively over now that everything is finished, everything has been decided.

The feeling we have before Michelangelo’s great wall painting is a terrible one. It is the feeling Pope Paul III Farnese must have had when – so the story goes – he knelt dismayed, with tears in his eyes, on that day of October, the eve of All Saints’ Day of the year 1541, when the Judgement was uncovered.

Some fundamental iconographic keys are needed to understand the Judgement. The focus of the composition, almost the motor that drives the terrible machine, are the angels playing trumpets who call the dead to Resurrection; a tangle of naked young men displaying two open books: a small one calling the righteous to heaven, and a large one condemning the damned to Hell. Because many are called but few are chosen.

Presented as evidence at the Court of Judgement are the instruments of the Passion of Christ kept by a turbine of Angels in the high wall of the fresco: the Cross and the Scourging Column, the crown of thorns, the sponge soaked in vinegar.

Because Christ died for us, we shall be judged by the cross. According to our fidelity to the Cross, we shall be saved or damned. This is the meaning of the Passion symbols.

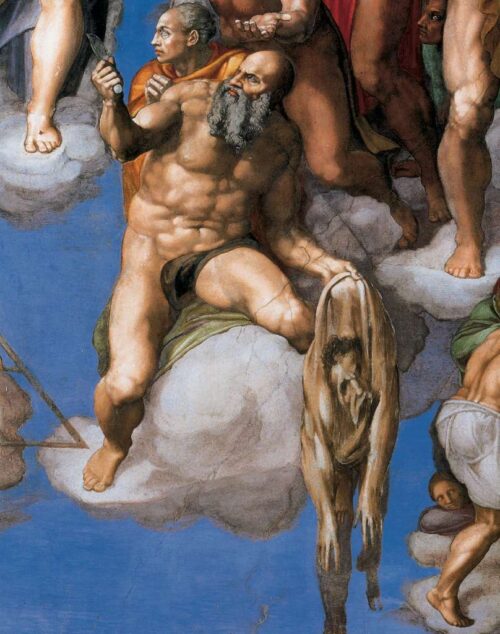

Michelangelo’s fresco shows the triumphant Church arranged in a semicircle around the celestial Judge. It also shows St Bartholomew with his own skin, often recognized as being a self-portrait of Michelangelo himself, Angels and Demons contending the resurrected and the furnace of Hell bubbling and flaming up from the cracks in the earth.

At the Last Judgement, we appear naked, in the fulness of youth and physical fitness to return to the Most High the splendor of appearance he gave us by making us in His image. This is flawless from a theological point of view. The fact remains that all this display of breasts, buttocks, and genitals appeared disturbing and unacceptable to many.

The successor of Paul III quietly tried to suggest to Michelangelo to hide all this nakedness somehow. The ironic and contemptuous reply of Michelangelo, so Giorgio Vasari tells us, has remained famous: “ Tell his Holiness that this is a small matter and can easily be set straight. Let him look to set the world in order: to reform a picture costs no great trouble”. In actual fact, until Michelangelo lived, no one dared touch his masterpiece. Only after his death (1564) were the parts considered most “ scandalous” repainted over and covered with drapery. This thankless task was given to the painter Daniele da Volterra, an excellent artist who, because of this was nicknamed “braghettone” (the pant painter) – his fame thus marked forever.

Michelangelo’s Judgement has been studied, commented and celebrated in all the languages of the world. The printed works dedicated to him are so many that they could fill an entire library. Among all the options that to us seem most fulminating and final is that which a brilliant Florentine spirit, Anton Francesco Doni, a friend of Michelangelo, entrusted to a letter dated 1543, two years after the inauguration of the fresco. So writes Doni to Buonarroti: “ when the Final Judgement, the real one, comes, our Lord will prefer that which Michelangelo has painted because even he could hardly imagine a better one”. So writes Doni and this hyperbolic paradox, almost verging on irreverence, is the most brilliant token of appreciation that has ever been made of the Judgement.

Restoration of the frescoes was begun in June 1980, under the direction of Fabrizio Mancinelli, and carried out by the Vatican restorers led by Gianluigi Colalucci. On 8 April 1994, a solemn mass celebrated by Pope John Paul II marked the end of the most sensational and at the same time most criticized restoration job of the century.

Now that we finished our tales about the decoration of the most famous chapel in the entire world, is time for you to book one of our Vatican Tours and discover much more details about the Sistine Chapel,

click HERE